Back to the Annual Report Contents and Home page

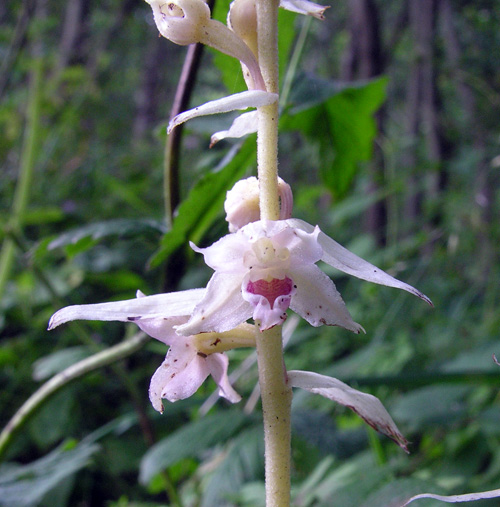

I found an unusual helleborine near Bank Wood, Whitwell, in August 2008. It appeared to be a completely white common (or broad-leaved) helleborine Epipactis helleborine. I originally thought the plant was an albino, but closer examinations showed that although there was no green (chlorophyll) there was some pink colouring in the flowers. There were two stems growing from a common point, so I assume this was all one plant. I posted a couple of pictures on the UK Botany forum, and the experts there came up trumps.

So, with thanks to Malcolm Storey, Rodney Burton and others I now know this is known as ‘hypochromic’ – which I think means ‘lacking in colour’ although my Latin’s not very good. Malcolm says “Interesting. This is more common in Violet Helleborine where it is a named variety. You get intermediates – there are photos on BioImages of a pink-tinged stripy one that looked like a giant Tradescantia!”

Rodney says: “There are two characters, albinism which is a total lack of pigments, including chlorophyll, which in Epipactis is very rare, and possibly due to overactivity on the part of the symbiotic fungi, and hypochromy, in which the expression of chlorophyll pigmentation is suppressed, but the expression of anthocyanin, responsible for the violet colours, is not. The latter is due to a genetic accident, and also weakens the plant generally. (Source: P. Delforge, Guide des Orchidées d’Europe).

I wondered if it might be something to do with a failure of the fungal

associate, but I was put right: “Quite the reverse. It’s the fungal host

that’s keeping it alive! It’s a failure of the plant to develop

chloroplasts. You see this not uncommonly in seedlings of other plants when

you sow seeds in a tray etc. but they usually die before attaining any size.

In this case the support from the fungus lets them grow and flower – the

flowers will probably shrivel before they ripen seed....

... without chlorophyll, the plant can’t photosynthesise, so it’s most

likely it will be too short of carbohydrate to produce nectar (or any nectar

it produces will be too weak) so the flowers won’t get visited.”

Sean Cole came up with “This is the first time I have seen a plant, or a photo of one, this colour. Turner Ettlinger (1997) notes a var called albifolia, and his pictures show pale foliage with pinkish flowers and pale green bracts.

I believe this one of yours looks to be at the extreme end of this var....A beautiful thing....

As you will know, E. helleborine is allogamous (cross-pollinated), so for this plant to produce seed it would have to have some way of attracting wasps (commonest pollinator for this species). As it is presumably not giving any colour signals, it would have to rely on smell and/or the production of nectar.

If you check the flowers you will easily see whether they have been visited as the pollinia will have been removed wholesale along the viscidia. If they have produced pollen but not been visited, the pollen will crumble with age and drop onto the stigma (but in small quantities due to the shape and angle of the rostellum) with a chance of self-pollination.....”

I did have a closer look but wasn’t really able to determine if this was the case.

Mark Lynes visited the plants and sent me this note, along with some wonderful photos (far better than mine) two of which are reproduced here, with permission (and thanks).

“Interestingly whilst I saw no insects visiting the flowers, there was no nectar in the hypochile, several small woodlouse like crustaceans were actively exploring the open flowers. Woodlice, of course, feed on dead & decaying matter. Just a thought...”

Pictures © Mark Lynes 2008

Sean visited the site with me, and sent this report:

“On your plant the pollinia were tucked under the anther cap and had not dropped onto the clinandria. It is there that they stick to the exuded viscidium which allows them to be taken by insects. A wasp visiting the plant would not come into contact with the pollen at all. Similarly, the receptive stigma was not sticky, as with other plants which are “on heat”, so an insect visiting from another plant with pollen attached to it would not deposit that pollen onto the stigma as it wouldn’t stick. Additionally, the lack of nectar (I think it was decided there was none in the hypochile?) means that the flowers would not attract the wasps in the first place.

Allogamous plants which do not get visited by insects have a back up method (which is the start of a process that leads to new, self-pollinated species) whereby the pollen with age becomes frious and breaks apart, dropping onto the stigma of the same flower. Again with this plant that couldn’t happen because the pollen weren't exposed beyond the rostellum.”

I monitored the plant over the next few weeks, and sadly the seedpods totally failed to develop; the whole plant rapidly became ragged and eaten (by slugs I think) then vanished altogether – the robust normal plant growing alongside it developed normally, indeed the seedpods were still evident into October.

I have marked the spot and will visit it next year to see if this very interesting plant re-appears.

Gill Smith 20th Oct 2008

Back to the Annual Report Contents and Home page